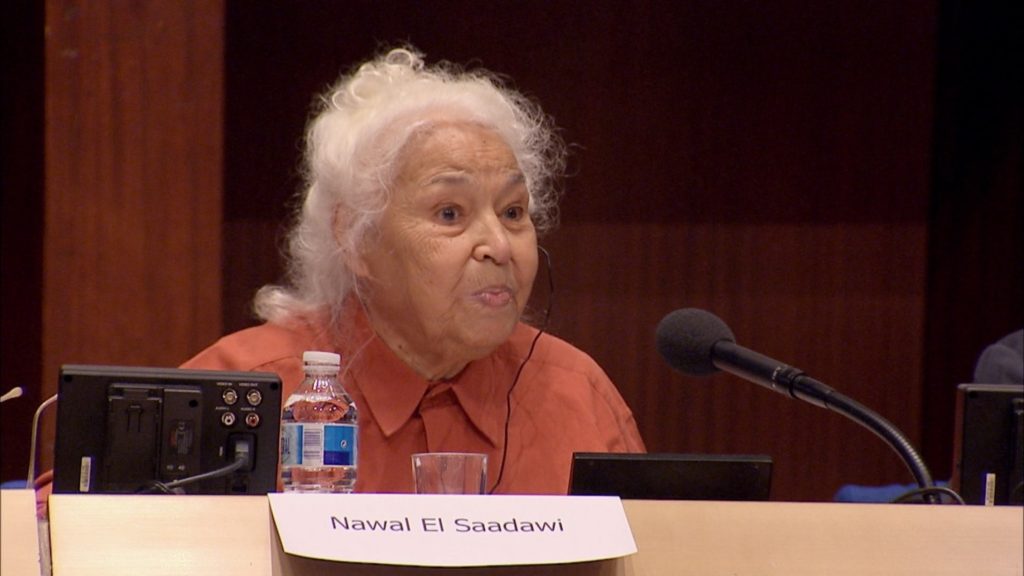

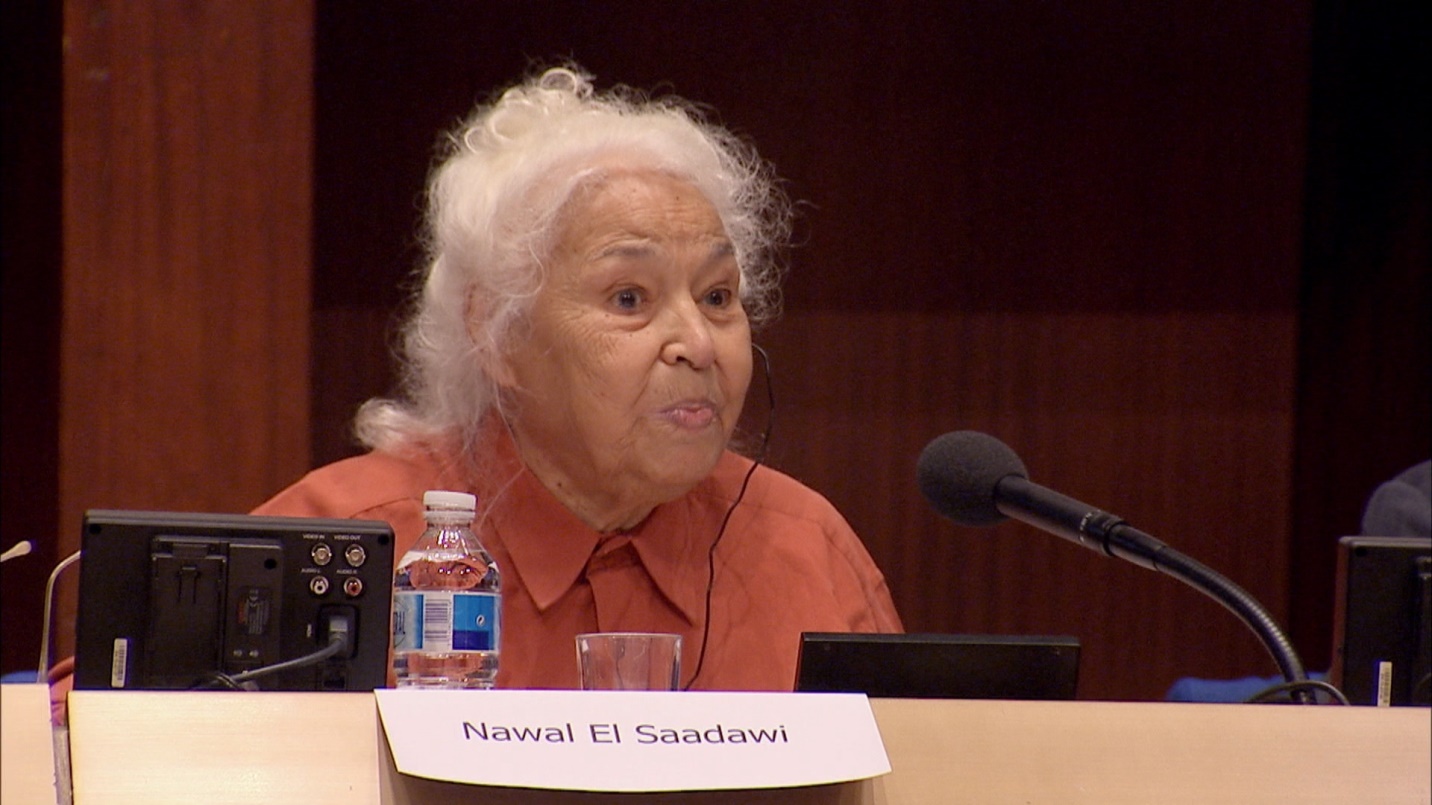

Nawal El Saadawi is a leading Egyptian feminist, sociologist, medical doctor and militant writer on Arab women’s problems. She is one of the most widely translated contemporary Egyptian writers, with her work available in twelve languages.

Nawal El Saadawi was born in 1931 in Kafr Tahla, a small village outside of Cairo. El Saadawi was raised in a large household with eight brothers and sisters. Her family was relatively traditional, El Saadawi was “circumcised” at the age of six, and yet somewhat progressive, El Saadawi’s father insisted that all of his children be educated. El Saadawi describes her mother as “a potential revolutionary whose ambition was buried in her marriage.” Her mother died when she was 25, and her father shortly thereafter, both unable to witness the incredible accomplishments their daughter went on to make.

Despite limitations imposed by both religious and colonial oppression on rural women, El Saadawi attended the University of Cairo and graduated in 1955 with a degree in psychiatry. After completing her education, El Saadawi practised psychiatry and eventually rose to become Egypt’s Director of Public Health. El Saadawi met her husband, Sherif Hetata, also a doctor, while working in the Ministry of Health, where the two shared an office together. Hetata shared El Saadawi’s leftist views, himself having been imprisoned for 13 years for his participation in a left-wing opposition party.

Since she began to write over 25 years ago, El Saadawi’s books (27 in all) have concentrated on women, particularly Arab women, their sexuality and legal status. From the start, her writings were considered controversial and dangerous for society and were banished in Egypt. As a result, El Saadawi was forced to publish her works in Beirut, Lebanon. In 1972, her first work of non-fiction, Women and Sex, which as the title suggests, dealt with the highly taboo subject of women and sexuality, and also the sensitive subjects of politics and religion. This publication evoked the anger of highly placed political and theological authorities, and the Ministry of Health was pressured into dismissing her. Under similar pressures, she lost her post as Chief Editor of a health journal and as Assistant General Secretary in the Medical Association in Egypt.

From 1973 to 1976 she researched women and neurosis in the Ain Shams University’s Faculty of Medicine. Her results were published in Women and Neurosis in Egypt in1976, which included 20 in-depth case studies of women in prisons and hospitals. This research also inspired her novel Woman at Point Zero, which was based on a female death row inmate convicted of murdering her husband that she met while conducting the research.

In 1977, she published her most famous work, The Hidden Face of Eve, which covered a host of topics relative to Arab women such as aggression against female children and female genital mutilation, prostitution, sexual relationships, marriage and divorce and Islamic fundamentalism.

From 1979-180 El Saadawi was the United Nations Advisor for the Women’s Program in Africa (ECA) and the Middle East (ECWA).

Later in 1980, as a culmination of the long war she had fought for Egyptian women’s social and intellectual freedom, an activity that had closed all avenues of official jobs to her, she was imprisoned under the Sadat regime, for alleged “crimes against the state.” El Saadawi stated “I was arrested because I believed Sadat. He said there is democracy and we have a multi-party system and you can criticise. So I started criticising his policy and I landed in jail.” In spite of her imprisonment, El Saadawi continued to fight against oppression. El Saadawi formed the Arab Women’s Solidarity Association in 1981. The AWSA was the first legal, independent feminist organisation in Egypt. The organisation has 500 members locally and more than 2,000 internationally. The Association holds international conferences and seminars, publishes a magazine and has started income-generating projects for women in rural areas. The AWSA was banned in 1991 after criticising US involvement in the Gulf War, which El Saadawi felt should have been solved among the Arabs.

Although she was denied pen and paper, El Saadawi continued to write in prison, using a “stubby black eyebrow pencil” and “a small roll of old and tattered toilet paper.” She was released in 1982, and in 1983 she published Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, in which she continued her bold attacks on the repressive Egyptian government. In the afterword to her memoirs, she notes the corrupt nature of her country’s government, the dangers of publishing under such authoritarian conditions and her determination to continue to write the truth:

Even after her release from prison, El Saadawi’s life was threatened by those who opposed her work, mainly Islamic fundamentalists, and armed guards were stationed outside her house in Giza for several years until she left the country to be a visiting professor at North American universities. El Saadawi was the writer in residence at Duke University’s Asian and African Languages Department from 1993-1996. She also taught at Washington State University in Seattle.

El Saadawi continues to devote her time to being a writer, journalist and worldwide speaker on women’s issues. Her current project is writing her autobiography, labouring over it for 10 hours a day.