By: Faridah Mugimba Kakyama

African pension funds are starting to invest in infrastructure projects on their underdeveloped continent. The African Development Bank hopes the deepening pool of homegrown savings can fill the $45 billion hole it sees in annual infrastructure financing needed in Africa.

“It’s an unprecedented chance to make the investments in infrastructure and other sectors that the continent so desperately needs,” said David Ashiagbor, who runs a division of the bank devoted to developing financial markets in Africa. Until recently, most pension funds in Africa were hesitant to invest in infrastructures such as roads, railroads, and ports. Tying up cash in decade-long projects seemed unnecessarily risky while strong economic growth was driving up local stock markets.

Africa’s economy has recently grown by about 5% annually thanks to strong oil and mineral output as well as the rise of a nascent consumer class. The continent’s sovereign bonds were also generating strong returns because they are issued at a premium that reflects their riskiness relative to developed-market issuers like the U.S. That strategy is still working—almost too well. African pension funds that focus on stocks and bonds in their home markets have swelled. Namibia’s government pension fund manages assets worth 80% of the southern African country’s gross domestic product. Botswana’s local stock-and-bond holdings equal 40% of the diamond-rich nation’s GDP.

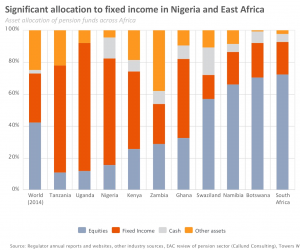

In Africa bonds and equities remain the two predominant asset classes for pension funds. While globally there is a larger allocation to equities (42.3%), the picture in Africa is more disparate. Broad asset allocation in sub-Saharan Africa has favoured equities that have shown a steady increase alongside the development of capital markets and regulatory change.

In Nigeria and East Africa, asset allocation is dominated by fixed income allocations, which predominantly constitute local bonds. When viewed alongside the high asset-growth in these regions, this is illustrative of regulation as well as local investment opportunities. This typifies one of the larger challenges pension funds face; identifying appropriate local investment and development opportunities at the same pace as asset growth.

RisCura analysis Local regulation remains one of the main drivers of asset allocation. While much of African regulation is supportive of local investment, there are often significant differences between the regulatory allowances for pension funds, the size of local capital markets and actual portfolio allocations.

Pension Focus November Magazine 2016 explains significant differences between the regulatory allowances for pension funds, the size of local capital markets and actual portfolio allocations. This is reflective of a number of factors, including familiarity with alternative asset classes, such as private equity, development of local capital markets and availability of investment opportunities. In many countries, assets are growing much faster than products are being brought to market, limiting investment opportunities if regulation does not allow for pension funds to invest outside of their own countries.

As pension assets continue to grow and international development assistance decreases, African pension funds have a pivotal role to play in facilitating inclusive growth and social stability. Larger pools of capital allow for investment in economic and capital market development locally and on the continent. Africa would benefit from local investment in longer term projects, including infrastructure. Local institutional investors lend credibility and a measure of validation and often serve as a catalyst for greater external interest. Local investors also allow global peers to leverage local knowledge and networks. With longer investment horizons, pension funds can serve as anchor investors for infrastructure and social development projects.

While investment in private equity in emerging markets has historically come from DFIs, pension funds are slowly joining in. A number of countries including South Africa, Botswana, Nigeria, and Namibia have led the way of alternative asset classes such as private equity. South African pension funds, for example, have been active in African private equity investment, both locally and across the continent, enabled by regulatory change. Since 2011, Regulation 28, which is the governing law for pension funds in South Africa allows up to 10% of pension assets to be invested in private equity, an increase from the previous 2.5% allowance for all ’other’ asset classes. Nigeria first introduced broad pension reforms in 2004 when the National Pension Commission (PenCom) was established and laws were passed introducing mandatory contribution schemes for all unfunded public and private sector employees initiating the change from DB to DC schemes. Regulation in 2010 set the limit for private equity at a prudent 5% and also imposed certain minimum requirements for such investment including a minimum ten years’ experience for investment professionals, a minimum 75% exposure to domestic Nigerian assets and required general partner (GP) investment. Draft regulation released for comment in early 2015 proposes to further relax these limits. While this enables investment, the requirements are quite prescriptive and have hampered practical implementation.

Nigeria is due to pass further legislation that will make provision for additional permissible investment instruments. This is expected to support the development of local capital markets and increase allocations to equity markets. Regulation can also enable regional and international diversification. Namibia, for example, allows up to 35% of assets outside the Common Monetary Area (Lesotho, South Africa, Namibia, and Swaziland), however with a limit of 30% outside Africa, while Botswana allows up to 70% investment abroad. This allows pension funds the freedom to find suitable investment opportunities without being constrained by the current limitations of local market development. This is in contrast with East African countries such as Uganda and Tanzania where offshore investment is not allowed, although in the case of Tanzania it is unclear whether the restriction applies to a country or regional level (East African Community).

African Labour trends determine Life savings

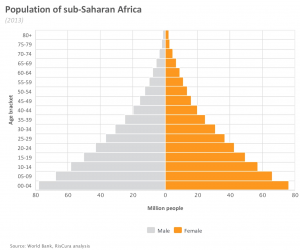

While Africa proves no exception to trends of universally ageing populations, the continent still has a young population compared to the rest of the world. Uganda, for example, has a median age of 15 years, and also the youngest population in the world, with Uganda at the lower end, to 40 years of age or more in several European countries and Japan (CIA, 2013). There are a number of factors driving this demographic trend, amongst them higher than average population growth on the continent and an increase in life expectancy. Over time, a combination of these factors is expected to increase not only the percentage of the labour market population in Africa but also the number of years spent in retirement, creating greater demand for increased coverage and adequate pension provision. The combination of increased life expectancy and working age population is likely to lend strong support to growth in pension fund assets on the continent. Working age population in Africa will increase, as will the number of years spent in retirement.

Working age population in Africa will increase, as will the number of years spent in retirement